Japanese defeat at Midway on 4-6 June 1942 brought very painful understanding of the importance of the Kido Butai - Carrier Task Force. So Japanese Navy very quickly created a plan to rebuild it, adopting new carrier strength expansion plan on 30 June 1942.

According

to the plan, main strength of the new Kido Butai were to compose improved

versions of already existing designs: 5 large carriers of the “Taiho” class

(with armored flying deck) and 13 medium carriers of the “Unryu” class. To together

with original “Taiho” and “Unryu”, that were already building, it provided for

20 carriers = 3 heavy and 7 medium carrier divisions.

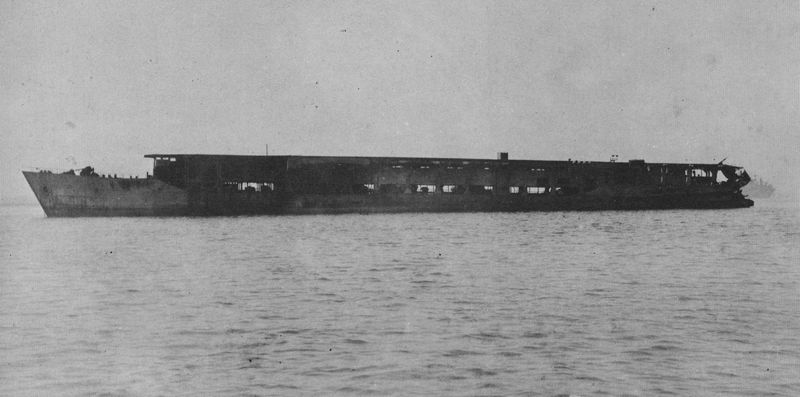

Aircraft carrier “Taiho”

Aircraft carrier “Unryu”

For details

see attached table 7.5 from the book “Japanese Cruisers of the Pacific War” by

Lacroix and Wells (with some of my clarifications added):

The problem

was – building large warship is neither fast nor easy. As a result main

strength of the plan to be completed only in 1947(!). So IJN had to improvise,

doing quick conversion of other ships in order at least to regain pre-war

carrier force strength before new carriers will enter service. 6 ships were

chosen for conversion plus 3 more were added later. Other battleships and heavy

cruisers were considered, but eventually ideas of their conversion were

abandoned due to the need of those ships as they were.

As you can

see, according to the above table IJN can’t even achieve December 1941 level of

aircraft strength aboard fleet carriers (that is, excluding 4 slow CVs: “Shinyo”

and “Taiyo” class) before mid-1944. And IJN expected the number of US fleet aircraft

carriers (CVs, CVLs) will be 12 by the end of 1943 (compare with 7 CVs in

December 1941).

So the

question of “quick and dirty” increase of carrier strength till 1945 at least was

of paramount importance for the IJN. There is little use of new carriers if the

fleet is already defeated. As it happened in real life in 1944. Of course, lack

of carrier capacity is definitely not the only reason for Japanese defeats, yet

it’s one of the obscure ones, usually limited to the usual explanations of

Japan’s industry problems. But industry did its best: “Taiho” and first 3 “Unryus”

were completed before planned dates. Yet it was still too late, as only “Taiho “was

able to take part in Philippine Sea Battle against US carrier task force in

June 1944.

That’s why

the first two years of IJN carrier strength expansion plan of June 1942 worth more

careful study. Could IJN do better

there, than in the original plan?

All 1942 FY

ships of the plan are pre-Midway plans and little extra could be done here (to

be precise “Chuyo” orders to start conversion were issued after Midway battle

(on 21 June 1942), but planning for conversion was obviously done before the battle).

Among 1943

FY ships initially there were only two warships: “Chitose” and “Chiyoda”. They

were both built as seaplane carriers (CVS) with construction allowing for conversion

into carrier. So they were to be converted into CVLs which can carry some 30

planes each. Looks good – until we find out, that at the same time IJN

desperately tried to attend lack of seaplane capacity of the fleet. Cruiser “Mogami”

and oiler “Hayasui” received expanded seaplane facilities. Later on “Ise” class

battleships and “Tamano” class oilers were also to receive capability to carry seaplanes

and even launch carrier aircraft from special trollies. All this added no

carrier decks, but at the same time relieved carriers from such tasks as reconnaissance,

anti-submarine patrols, etc. And new seaplane fighters and dive-bombers allowed

for support of the regular carriers in combat. Each plane, doing such job from

the board of the CVS, relieved a plane aboard CV for other mission.

Now the mystery:

why to convert existing seaplane carriers into regular carriers if you still need

seaplane carriers??? In mid-1942 there were 3 high-speed CVS in the IJN:

“Chitose”, “Chiyoda” and “Nisshin” (last two were converted into midget

submarine carriers, but still could carry seaplanes on the upper decks).

Instead of quick re-conversion of two ships into CVS, “Chitose” and “Chiyoda”

were converted into carriers while “Nisshin” remained to be used as fast transport

without any plans for its CV conversion. In my opinion, “Chitose”, “Chiyoda”

and “Nisshin” with some 20 seaplanes each would’ve been way better addition to

the fleet, then converted “Mogami”, “Ise” and “Hyuga”. And the conversion times

will be way shorter.

Now about

other ships in this plan: “Kaiyo” (ex-“Argentina Maru”) and “Brazil Maru”.

Together with other 4 CVs, converted from merchant ships, they are often called

“escort carriers” – which is incorrect. Those 2 ships were to receive destroyer

turbines so they could operate with “Junyo” class CVs and older battleships.

But this never happened. Just like planned conversion of 3 ships of the “Asama

Maru” class along the same lines. Some other ships can follow, each carrying

c.20 planes. Of course, those ships weren’t as good, as purpose-built carriers.

But they were there and could bring up IJN fleet carrier strength by 100-plus

aircraft by mid-1944.

Another mystery

is lack of progress with aircraft carrying fast oilers of “Hayasui” and “Tamano”

classes, also ordered in 1942. Of 15 ships planned only “Hayasui” was

completed. They were too complicated for mass production? – Why not to build

something similar on the base of standard 1TL wartime standard tankers?

Model of "Tamano" oiler

But the

biggest mystery of them all in this 1942 plan is a total lack of anything resembling

carriers, built on the hulls of wartime standard ships. After Midway there was

a special study about merchantmen, converted into carriers to transport

aircraft. Even if they had little value for the fleet battle, they can relieve

fleet carriers from transport missions, convoy escort and other secondary

duties. But only in 1944 few such ships were planned, but even then at first as

Merchant aircraft carriers, which continued to carry cargo and operated under

civilian command with small military aircraft detachment aboard. Only later some

of them become full-fledged escort carriers. The most surprising – the driving

force behind this was apparently not Japanese Navy, but Japanese Army.

One can say

all those change doesn’t matter. IJN was doomed to lose from the beginning of

the war due to the disparity of strength with its enemies. May be. But it doesn’t

mean we shouldn’t research the decisions made by the Japanese Navy to see if

they were optimal or not.

Eugen Pinak

23 October 2022

No comments:

Post a Comment