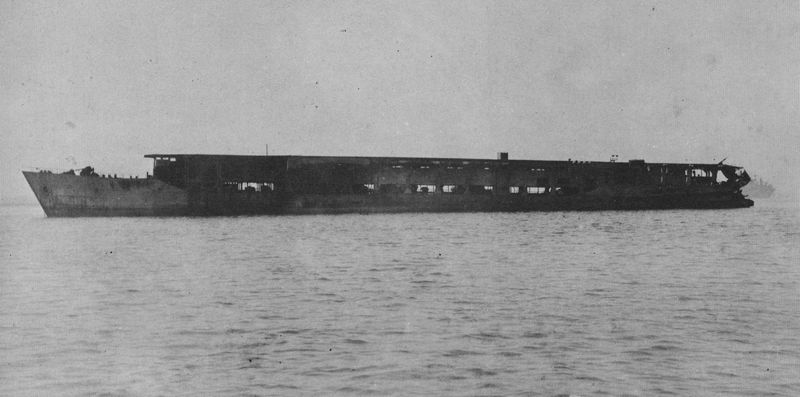

The box cover of one of the volumes of “Sensi Sosho”.

After the

surrender of Japan in World War II, the US intelligence personnel found

themselves in a very comfortable position. The US occupation

administration simply gave an order - and the Japanese authorities quickly organized

the writing of the history of the Second World War in the Pacific from the Japanese point of view in order to make it easier

for American researchers to work on American history of the Pacific War.

Unfortunately,

from the triad “fast, cheap, high quality – chose two of three” the Americans

decided to dispense with “high quality”. As a result, the first Japanese

history of WWII, better known by its name in English as “Japanese Monographs”, was

largely a victim of haste.

First, the

monographs differed in quality: from the general history of military

transport throughout the war to the description of the capture of a small

island. The monographs themselves were small at first, apparently due to the

tight deadlines for writing. Where it turned out to be necessary to describe a

serious issue, the authors worked in the style of “novel in the newspaper” -

they divided the topic into chapters and proceeded them in turn one by one. There was no unified editing of proofreading. Over time,

the haste has subsided, and later Monographs were begun to resemble monographs

in size and detailed description of the topic.

The

Monographs themselves are largely paraphrases or quotations from official

documents. Which is not surprising, since the authors simply did not have the time

for serious analysis and synthesis.

Moreover,

not everything, that needed to be written, was actually written. For example, there

is no Monograph on the Battle of Midway and the attack on Pearl Harbor (the

monograph on Pearl Harbor is actually just a collection of documents). As I

understand it, this was due to the fact that the people, who could write these

monographs, were working directly with the Americans. In addition, not

everything, that the Japanese wrote, was translated into English.

The English

language of monographs, by the way, is a problem in itself. Of course, even a

bad translation is better than no translation - which explains the popularity

of monographs among non-Japanese researchers to this day. But this does not

change the fact that the Monographs were translated by a variety of translators,

who did not worry about the consistence of the translation of terminology, place

names, etc. Moreover, there are specific errors in the translations, especially

in the names of ships and the names of people, which are not so easy to

translate from Japanese.

As a

result, in the mid-1950s US personnel was tasked with editing and

proofreading the translations of some of monographs. But interest in them

faded, so only part of the monographs was edited.

Brief

history of creation, list and description of monographs (sometimes very

critical):

https://oregondigital.org/sets/easia/oregondigital:df72dt655#page/1/mode/1up

Texts of Japanese Monographs online:

https://pacificwararchive.wordpress.com/2019/01/27/japanese-monographs/

==========

The

shortcomings of the Japanese Monographs were already obvious at the time of

their writing, so the Japanese Institute of Military History begun to make a better quality history of

the Pacific War. The process was led by Hattori Takushiro, former Chief of

Operations of the General Staff of the Imperial Japanese Army.

8-volume work

“The Complete History of the War in Great East Asia” = 大東亜戦争全史, published in 1953-56, turned out

to be a book of a completely different level than the Japanese Monographs - the

quality of the authors’ work is evident here. But there are questions here as

well. First, history is written almost exclusively from the Army's point of

view and at a strategic level. There were simply not enough resources to

describe tactical actions. Secondly, the officers of the General Staff were not

inclined to particularly analyze or criticize their own actions.

Nevertheless,

this work was a quality research which turned out to be quite popular for a book on such peculiar topic. Japanese edition has been reprinted twice and had also been translated into English and Chinese. Its’ abbreviated version was translated into Russian under the title “Japan at War” (very rare thing for Japanese book). However, not everything

was translated - the tender souls of Soviet propagandists could not stand the

encounter with the real description of the Japanese campaign in Manchuria in

1945, so they simply threw it out of the book, replacing it with a condemning philippics against “falsifications” in the style of the editorial of the “Krasnaya Zvezda” newspaper (official newspaper of the Soviet Army).

==========

Meanwhile former officers of the Imperial Japanese Navy also worked on better quality history of the Pacific War, named “Nippon Kaigun Senshi” = “War History of the Japanese Navy” = 日本海軍戦史. In 1950 at least 11 small volumes were published. But those volumes were, in fact, improved versions of the Japanese Monographs, which hardly looked impressive compared to “The Complete History of the War in Great East Asia” then in the making. That’s why this project was abandoned.

==========

It is clear

that the Institute of Military History was not going to stop after the release

of Hattori’s book. There, work continued on the new Japanese history of WWII,

known as the “Senshi Sosho” = “Military History Series” = 戦史叢書. Work has accelerated sharply

after most of the documents, confiscated by the USA after the war, were

returned to Japan in the mid-1960s.

But

Japanese military historians were not going to limit themselves to documents.

Numerous veterans were involved in the work, who could use their diaries

(during WWII, keeping a diary was considered almost an integral part of the

life of an educated Japanese) and documents in their possession (which sometimes were not available elsewhere). Moreover, draft versions of the chapters of the

new history were actively discussed, and veterans, who were directly related to

these events, also participated in the discussions.

The first

volume of “Sensi Sosho” was published in 1966, the last (102nd) - in 1980. 2

more volumes with collections of documents were published in the mid-1980s.

The work on

“Sensi Sosho”, which lasted for almost thirty years, brought very positive

results. This time both army and navy points of view on the war were recorded

for the posterity. In these volumes there was a place not only for strategies,

not only for operations, but also for describing actions at the tactical level.

A huge advantage compared to previous histories was that at least some mentions

of the sources of the information have finally appeared which were not present in

previous versions.

But in

fairness, it should be noted that this version of Japanese official history was

not without flaws. A very sad division into history from the Army point of view

and history from the Navy point of view has been preserved. One and the same

operation can be described in two volumes: army and navy - and described in

different ways. And sometimes aviators also insert their point of view. At the

same time, even in dry lines, one sometimes feels a desire to hurt, to show

flaws of the opposite service.

The

Japanese did not succeed in creating a single, unified concept of the description

of the Second World War in the Pacific. Each volume is a “thing in itself”, and one volume

may well contradict with another.

It would be

useful to note the simple fact that the history of the war, written by the

participants, contains a lot of valuable details - but usually completely

devoid of any critical view of events. Not every person is able to engage

in self-criticism, while understanding perfectly well that it will be recorded in

the history book. On the other hand, given the paucity of the documents,

available to the authors of official history, the mass recruitment of veterans with

their diaries/documents was the best way to solve the problem. And for a historian, the

saddest thing is the lack of a full-fledged reference apparatus, which makes it

very difficult to verify the source of the particular information.

Despite its historical value, “Senshi Sosho” has hardly been translated into

other languages. One volume (about the “Battle of a Hundred Regiments” in North

China) was translated into Chinese in the Peoples Republic of China, and four

complete volumes plus parts from five other volumes were translated into

English.

Text of all volumes of "Senshi Sosho" in Japanese:

http://www.nids.mod.go.jp/military_history_search/

A) Translation on my web site:

Volume 24 "Naval Offensive Operations towards the Philippines and Malaya"

(1941-1942) - published on my web site with the kind permission of the

translator Pedro Brandão from Portugal:

https://rikukaigun.org/SS-24/SS-24_Philippines-Malaya.htm

B)

Australian translation (parts of Volume 14 and Volume 28 on IJA

operations in Papua-New Guinea):

http://ajrp.awm.gov.au/ajrp/ajrp2.nsf/Web-Pages/JapaneseOperations?OpenDocument

C) US translations - partial - by Rear Admiral Edwin T. Layton:

Volume 49 "Naval Operations in the South East Area Vol. 1" (incomplete):

https://www.usnwcarchives.org/repositories/2/archival_objects/58379

Volume 83 "Naval Operations in the South East Area Vol. 2" (Until the Withdrawal

from Guadalcanal):

Part 1: https://www.usnwcarchives.org/repositories/2/archival_objects/58385

Part 2:

https://www.usnwcarchives.org/repositories/2/archival_objects/58386

D)

Dutch translations:

Volume 3 "The invasion of the Dutch East Indies" (IJA operations):

https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/32880

Volume 26 "The Operations of the Navy in the Dutch East Indies and the Bay of

Bengal" (IJN operations):

https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/28411

Volume 34 and part of the Volume 5 "The Invasion of the South" (Operations of

the IJA Aviation):

https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/48379

===============

Unfortunately, this is where the Japanese decided to end the official writing of

the history of WWII in the Pacific. With the exception of identifying and

correcting errors in the “Senshi Sosho”, there is no new work on the academic

history of World War II in Japan.

==============

Unfortunately,

this is where the Japanese decided to end the official writing of the history

of WWII in the Pacific. With the exception of identifying and correcting errors

in the “Senshi Sosho”, there is no new work on the academic history of World

War II in Japan.